|

My Erythronium "Big Year"

By Ed Alverson

Eugene, Oregon, USA

Part 2: April 2005.

The first few weeks of spring are the peak season of bloom for the native erythroniums that grow at lower elevations. At the same time, weather during late March and early April is still somewhat variable on the west coast, with sunny spells interrupted by episodes of rainy or showery weather. This presents a challenge to the Erythronium explorer since soggy Erythronium flowers do not display their charms to the fullest. In 2005 we experienced an unusually dry and mild winter in the Pacific Northwest, but as soon as spring arrived the weather turned, and the next two months were unusually cool and wet. Still, I managed to find enough days of decent weather to continue my Erythronium quest.

Our local wild species of Erythronium in the Eugene area is Erythronium oregonum. Most populations fit best under ssp. leucandrum because they have creamy to almost yellow tepals, and pale (usually cream to light yellow) anthers. In Oregon, populations that have clear white tepals and yellow anthers (ssp. oregonum) are more often found in the Cascades and Coast ranges rather than in the lower elevation valleys, but in Washington and British Columbia only ssp. oregonum is found.

While it is certainly not as abundant as it once must have been, Erythronium oregonum is still fairly common around Eugene in local woodlands and other undeveloped habitats. While it is easily grown in local gardens, few people have the knowledge or patience to grow it well. But suburbia is full of surprises, and a mile or so from my home I came across an otherwise typical suburban yard that was literally bursting at the seams with E. oregonum. The entire front yard, except for the lawn and driveway (even the part outside the photo) is packed with thousands of erythroniums. Then, after the plants flower and go to seed, the yard returns to the monotony of a typical suburban landscape.

"Erythronium oregonum, Eugene, Oregon"

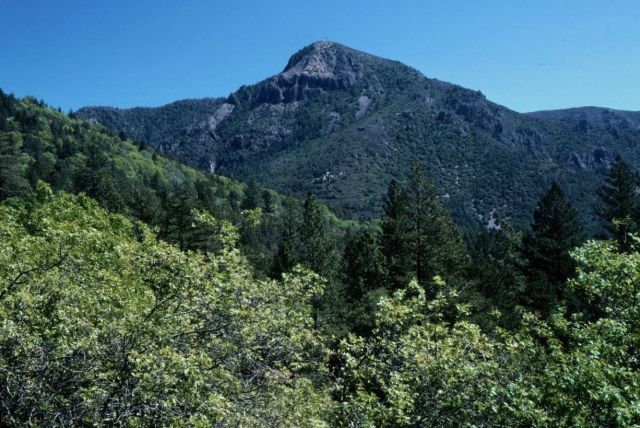

For my first out of town trip during April I traveled to northern California. On April 5th I set out to find the local endemic, Erythronium helenae. This species is found only in the vicinity of Mt. St. Helena, a 4343 ft. high peak located at the southern end of the Northern California Coast Ranges. This was a bit of a homecoming for me, since as a young child my family lived in Sonoma County, about 10 miles from Mt. St. Helena. Although the lower slopes are increasingly being cleared for vineyards (this is, after all, the famous Napa/Sonoma wine country), the upper slopes are still forested with a diverse mix of oaks and conifers.

"Mt. St Helena"

Unfortunately I did not have a lot of time to explore, but I did find several small populations of E. helenae at about 2300 ft. elevation along a narrow country road on the north side of Mt. St. Helena. Erythronium helenae is one of the white flowered species with golden centers and mottled leaves; it differs from E. californicum with its yellow anthers (instead of white) and shorter style. In cultivation, E. helenae increases vegetatively from corm offsets. E. helenae is also distinctive in having fragrant flowers. It is a beautiful species for cultivation; let's hope its few remaining wild populations can be conserved.

"Erythronium helenae"

My next goal was a search for Erythronium californicum. On this day, as on many other days during this filed season, I was following in the steps of Elmer Ivan Applegate (1867-1949), "Mr. Erythronium". Applegate was the grandson of famous Oregon pioneers of 1843, and spent much of his life exploring the west for erythroniums and other treasures of the native flora (a biography of Applegate can be found in volume 10 of the Native Plant Society of Oregon journal, Kalmiopsis). Applegate's 1935 monograph of the western North America Erythroniums is still the authoritative reference on the genus.

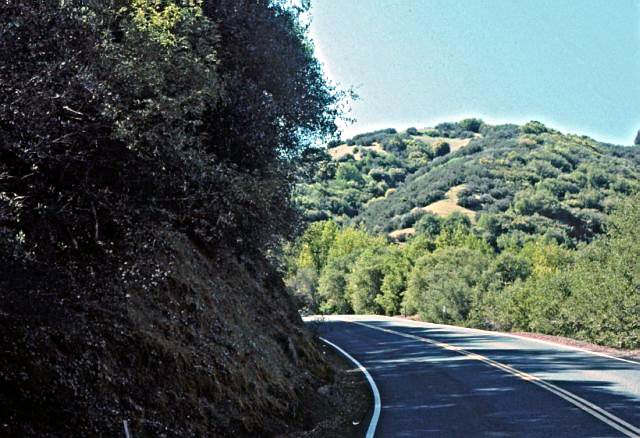

Much of Applegate's Erythronium field work was done later in his life, when he was in his 60's. On March 31, 1934, Applegate collected E. helenae at two localities on Mt. St. Helena, and then later in the day collected E. californicum in Lake County along the "Hopland Grade" between Clear Lake and Hopland (about 30 miles north of Mt. St. Helena). Seventy one years later (plus a week) I was also able to find E. californicum along the Hopland Grade, growing on north-facing roadside banks at an elevation of about 1700 ft. The vegetation here was evergreen oak woodland and chaparral, difficult to explore away from the road because of the abundance of both poison oak and "no trespassing" signs. It was a bit of a challenge to take photographs with traffic whooshing close by.

"Hopland Grade"

The tepals of these plants appeared to be rather creamy, almost lemony in color. Anthers are white. Note also the irregular red banding on the inside of the flowers; this is lacking in E. helenae. Also note the flower stalk with four flowers, branching from the middle of the stalk. One clump in the population (not illustrated) was evidently forming offsets. E. californicum, while endemic to California, is actually widespread erythroniums in the northern part of that state.

Erythronium californicum"

The following day, April 6th, I crossed the Sacramento Valley to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada to look for Erythronium multiscapoideum. There has been much discussion in print about a particular form of E. multiscapoideum that has informally been called "E. cliftonii" (not a validly published name) or Erythronium "Pulga form". The former name would honor Glen Clifton, an intrepid field botanist who has made a number of important botanical discoveries over the past 20 years. The latter name indicates where one would find it.

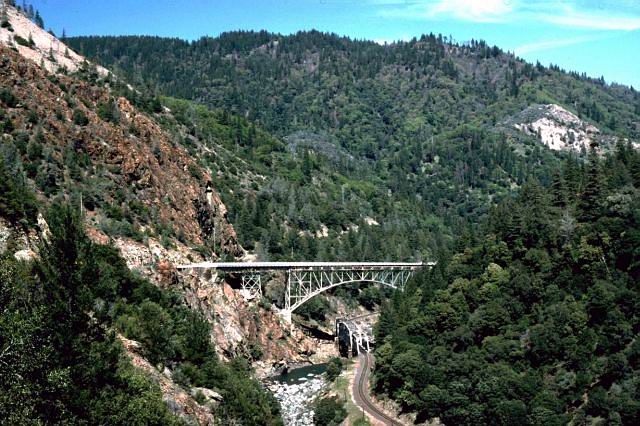

Pulga is a place name (there is no town to speak of) for a site along the Feather River miles east of Chico, in Butte County. The river flows in the bottom of a deep gorge, and the highway and railroad switch sides of the canyon at paired bridges. On the north side of the gorge are massive outcrops of ultramafic rock (serpentine or peridotite).

"Feather River Canyon"

I quickly found erythroniums growing along the side of the road. However, I was too late; at this low elevation (1600 ft.) the plants apparently flower in March. What a disappointment! Even in fruit, one can see the distinctive feature of E. multiscapoideum: The inflorescence is branched below the ground level, making it appear that each flower is on a separate stalk or scape (hence the name "multiscapoideum"). This character is unique to E. multiscapoideum.

"Erythronium multiscapoideum, in fruit"

The photo also shows a clump of leaves produced from offsets. This is confusing because, according to Applegate, typical E. multiscapoideum reproduces vegetatively from the ends of long runners (and is similar to some of the eastern North American species in this regard). This makes me wonder whether the offset character could be used to distinguish "cliftonii" from typical E. multiscapoideum, but I do not have enough experience with the plants in the field or in cultivation to say with certainty. Otherwise, "cliftonii" is considered to be a vigorous version of E. multiscapoideum, and has become popular among the erythronium cognoscenti.

Fortunately, I was not to leave disappointed, and found plants in flower on the shady, north-facing side of the canyon. In flower, it has real grace and charm.

"Erythronium multiscapoideum, in flower"

Back at home, I found time for another day trip on April 11th to search for Erythronium revolutum. Despite its wide latitudinal range (northern California to Vancouver Island, B.C.), E. revolutum is found only within about 30 miles or so of the coast. This is a zone of high rainfall and mild temperatures, which helps to explain its greater tolerance of summer water in gardens, compared to other western species.

Throughout most of its range, E. revolutum is actually a fairly uncommon plant in the wild. To find it, I headed in to the heart of the Oregon Coast Range about 40 miles west of Eugene. Though not lofty (peaks and ridgetops are generally between 2000 and 3000 feet) the Oregon Coast Range forms an incredible rugged maze of ridges and canyons. Once can hike up a remote canyon and feel you have landed in a lost world. It is an illusion, of course; the reality is that you are only a few miles away from highways and clearcuts, and the few designated wilderness areas are relatively small.

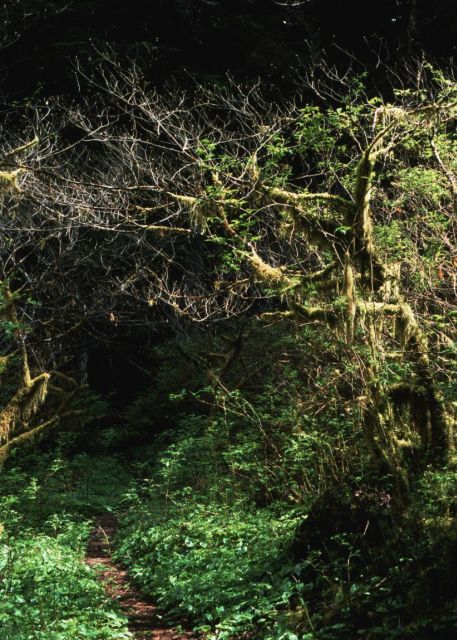

I made my way to a trailhead in the Siuslaw National Forest on the North Fork of the Smith River, which leads upstream through a lush canyon of mature and old-growth conifer forest. Epiphytic mosses grow especially prolifically in the humid atmosphere.

"North Fork of the Smith River"

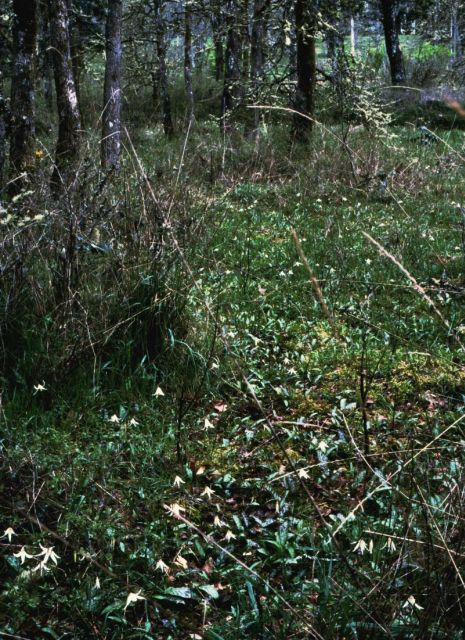

Erythronium revolutum seems to be somewhat particular in its habitat requirements. I found it growing either on the river bank close to the high water mark, or in brushy thickets of vine maple (Acer circinatum), seemingly avoiding the typical coniferous forest understory where other, more competitive understory species predominate. One advantage of living under hardwoods is the increased light that reaches the forest floor before the deciduous species leaf out.

"Vine maple thicket along North Fork Smith River trail"

Erythronium revolutum is the only pink-flowered species in western North America. It is, however, closely related to E. oregonum, sharing with it the character of flattened anther filaments. Natural hybrids between the two species have been found on Vancouver Island, B.C. (Allen and Antos, 1988). E. revolutum was also the first western species to be collected by European botanists, having been collected by Archibald Menzies in the vicinity of Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island, possibly as early as 1788. Lost in this mini-wilderness of the Smith River, one can easily imagine the landscape that presented itself to Menzies, David Douglas, and other early botanical explorers in western North America.

"Erythronium revolutum"

Returning to civilization, the next stage in my journey was visit a series of urban natural areas to look for Erythronium oregonum ssp. oregonum. On April 13th I headed back to the interstate freeway, this time driving north to western Washington State. I had been wanting for some time to explore Lackamas Park, a city park in Camas, Washington, located just east of Portland Oregon and Vancouver Washington. One has to appreciate a town that is named for a wildflower (in this case, the camas lily, Camassia quamash). Lackamas Creek, which flows over a waterfall and through a miniature gorge in Lackamas Park, is also named for the camas lily, in this case the term that was used by French-Canadian trappers. Camas was an important wild food plant for native Americans (who dug the bulbs in huge quantities, roasted them in underground pits, and then dried the cooked bulbs for long-term storage; Erythronium corms were also a common food item).

A portion of the park is called the "lily fields", where camas grows in abundance on an open, rocky slope. Fringing the lily fields, with the camas just starting to bloom, was a band of Oregon white oaks (Quercus garryana), transitioning beyond in to Douglas-fir forest.

"Lily Fields, Lackamas Park"

I found Erythronium oregonum ssp. oregonum growing in several large drifts under the oaks. The plants were just coming in to bloom so the flowers were not completely open to show the contrast between the white petals and the deep yellow anthers that distinguishes ssp. oregonum from ssp. leucandrum. As far as I know, only ssp. oregonum is found in the northern part of the species' range, from Washington north to British Columbia.

"Erythronium oregonum ssp. oregonum"

The substrate here is woodsy humus and soul pockets over bedrock. This provides good drainage, but given its ease of cultivation in normal garden soils, I suspect that the relative scarcity of E. oregonum in the northern part of its range is more a function of competition from other more vigorous native understory species.

Heading north toward Seattle, I made another stop at Fort Steillacoom Park near Tacoma. During the Pleistocene the retreating ice sheets left extensive plains of glacial outwash in the vicinity of Tacoma and Olympia, and these excessively drained soils developed into prairie and oak savanna vegetation. This area is now the last stronghold for prairie and oak habitats left in western Washington. I had first found Erythronium oregonum in Fort Steillacoom Park in 1986, and I was curious to see whether the population had survived (hopefully in this case, through benign neglect) over the past two decades. Fortunately, I readily found the same spot and there was still a thriving population of E. oregonum growing under an open canopy of oaks.

"Oak savanna, Fort Steilacoom Park"

Not only is this a vigorous population, but the leaves seem especially strongly mottled. Some of the plants show a slight brownish-purple tinge on the base of the outer side of the tepals, a character that seems to be correlated with the strong leaf mottling.

"Erythronium oregonum ssp. oregonum"

A brief visit with family in Seattle was really just a staging point for the next leg of my travels, to far eastern Washington to see Erythronium grandiflorum and its white-flowered relative, E. idahoense. Erythronium idahoense is a local endemic of the Palouse region of eastern Washington and adjacent northern Idaho. The Palouse is a rich agricultural region underlain by very deep loess soils. The natural vegetation was grassland and Ponderosa pine savanna, but most of the natural vegetation has been cleared for agriculture. The view from Steptoe Butte, in Whitman County, Washington, provides a good view of the lay of the land. This is a rather arid region, with a continental-type climate, cold in the winter and hot in the summer.

"View east from Steptoe Butte"

Steptoe Butte proper is too steep to farm, and has been protected as a state park. On the north side of the butte I found the white flowers of Erythronium idahoense, growing amongst native bunchgrasses and a few other early flowers such as Fritillaria pudica and Olsynium douglasii. This species has plain (un-mottled leaves), white flowers with a yellow center, and (usually) white anthers, although I did find a few plants with yellow anthers as well.

"Erythronium idahoense"

Elmer Applegate collected Erythroniums in the Palouse country in April 1931, just two years after E. idahoense was described as a full species by Harold St. John and G.N. Jones in 1929. Applegate visited the type locality for E. idahoense near Worley, Kootenai County, Idaho, which is about 5 miles over the state line from Washington. I was curious to see if E. idahoense could still be found in Worley, so I headed into Idaho. Amazingly, I found easily a nice patch of E. idahoense growing along the main highway right at the edge of town. The conditions were very windy, and a big thunderstorm was heading towards me, so I quickly took some photographs.

"Erythronium idahoense, type locality"

From Worley I headed back west to Spokane to spend the night. I was curious to see if I could observe the transition zone from E. idahoense to E. grandiflorum. This is how Applegate described the distribution of the two species in this region in his 1935 paper:

"In passing southward from Coeur d' Alene Lake, the whole country is yellow with E. grandiflorum to a point just south of Ford, where the species abruptly ends at the edge of an east and west road. On the opposite side of the road E. idahoense appears as suddenly and in as great abundance, everywhere - in the woods, in the open pastures, and in wheat and alfalfa fields, extending southwards without interruption for perhaps fifteen miles to the edge of the treeless plains in the vicinity of Tekoa in the northeastern corner of Whitman County, Washington. Even along the point of contact there is practically no intermingling of the two species of the region."

Sad to say, erythroniums no longer occur "in great abundance, everywhere" in this region, but instead are confined to patches of remaining suitable habitat here and there. I was not able to find a spot where E. idahoense abruptly ended and E. grandiflorum picked up on the other side of the road. However, driving NW from Worley towards Spokane, I only had to travel about 10 miles before I started seeing E. grandiflorum instead of E. idahoense.

Spokane has a wonderful urban natural area, the 500 acre Dishman Hills Natural Resources Conservation Area. A series of glacially scoured ridges and ravines rises to an elevation of 2400 ft., about 400 feet above the city. Vegetation is a mix of Ponderosa pine and grassy meadows, ideal habitat for erythroniums. My timing was perfect; it was April 14th and Erythronium grandiflorum was in full bloom. I arrived about an hour before sunset and was thrilled to find thousands of E. grandiflorum carpeting the ground in the glow of the setting sun.

"Ponderosa pine savanna"

In contrast to white-anthered population of E. grandiflorum I visited in the Columbia River Gorge in March, populations in the Spokane area belong to the variety with red anthers. This happens to be var. grandiflorum, because the first collection which represents the type specimen for the species is the form with red anthers.

"Erythronium grandiflorum var. grandiflorum"

"Dishman Hills, Spokane, Washington"

This is a good point to mention that the taxonomy of western erythroniums is still somewhat up in the air. While Applegate recognized E. idahoense as a separate species from E. grandiflorum, and also recognized the three anther color variants of E. grandiflorum as separate varieties, the author of the recent treatment of Erythronium for Flora of North America, Dr. Geraldine Allen, took a more conservative approach. Dr. Allen did not recognize the anther color forms as good varieties, and treated E. idahoense as Erythronium grandiflorum ssp. candidum. I am personally inclined to agree with Applegate; the three anther color forms of E. grandiflorum (red, white, and yellow) have rather discrete geographic ranges (although they may mix in areas where the ranges come together). The differences between E. idahoense and E. grandiflorum are no less than the differences between E. hendersonii and E. citrinum, which are morphologically identical except for aspects of petal and anther color. I might attribute the v

iewpoint of lumpers to a lack of experience with the plants in the field, for studying populations in nature is an important aspect of really understanding the species.

This brings to a close the first half of "My Erythronium Big Year". Starting in May, one must go into the mountains to follow the Erythronium season as moves up to progressively higher elevations.

References:

Allen, G.A. and J.A. Antos. 1988. Morphological and ecological variation across a hybrid zone between Erythronium oregonum and E. revolutum (Liliaceae). Madrono 35(1):32-38.

Applegate, E.I. 1935. The genus Erythronium: A taxonomic and distributional study of the western North American species. Madrono 3:58:113.

^ back to the top ^

|