|

My Erythronium "Big Year"

By Ed Alverson

Eugene, Oregon, USA

Part 4: June and July 2005.

By June, early spring is just a distant memory in our home gardens and local natural areas. The seeds of erythroniums that bloomed in March are beginning to ripen. Our thoughts turn to the pleasures of summer, the warm temperatures and long evening twilight.

But up in the mountains, the snow is still melting. Wildflowers that have been under a white blanket for seven or eight months are just beginning to awaken. And by traveling up in elevation, we can go back in time to have another chance to experience the pleasures of spring.

At least, in most years. In the Pacific Northwest, the winter of 2004-2005 was unusually dry, and the snowpack was only a fraction of its average depth. As a consequence, spring came early to the mountains. This was problematic for my erythronium quest, for it made it much more difficult to know when to time my visits. Flowering time data from "normal" years may not be so useful for planning my travels. So I just had to make my best guess for the timing of my visits.

On June 1st, I drove south to Ashland, Oregon. On the western rim of the Cascade Range is Grizzly Peak, home of Erythronium klamathense, and an outpost of montane flora overlooking the Bear Creek Valley, with the Siskiyou Summit and an endless series of botanically interesting ridges and valleys extending to the south.

Siskiyou Mountains and beyond from Grizzly Peak, Oregon. Mt. Shasta on the left, I-5 ascending to Siskiyou Summit on the right. Pilot Rock is the small knob in the center.

The summit of Grizzly Peak is more of a gently rolling plateau, a mixture of forest and open meadows, with a wonderful display of wildflowers. The elevation is nearly 6000 ft. (1800 m), but on June 1st the meager winter snowpack had nearly all melted. A few years ago a forest fire burned through some of the meadows and forest, leaving areas of silvery snags backing the colorful rocky meadows.

Meadows on Grizzly Peak

Unfortunately, nearly all of the erythroniums had finished blooming weeks earlier. In one little area, where the snow had taken longer to melt, I found a few remaining flowers of Erythronium klamathense. Though the specimens were rather scraggly, they were sufficient to show the pertinent characters: white flowers with a yellow center, fading to a slight purplish tint; yellow anthers; and (if you look closely) an undivided style. Not visible are the sac-like folds or appendages that are found at the base of the inner three tepals. Note also the plain, wavy-margined leaves, a feature that links E. klamathense to the Sierra Nevada species such as E. purpurascens.

Erythronium klamathense, Grizzly Peak

If you prefer, you can see better photos on Mark Turner's web site: http://www.turnerphotographics.com/nature/flowers/flowers2004/040512PilotRock/index.htm

Mark is the photographer for the recently published book, "Wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest" Mark's photos were taken at nearby Pilot Rock in May 2004. Note also that he also photographed a putative E. klamathense x hendersonii hybrid, and unusual combination that could only occur where the upper elevation limit of E. hendersonii overlaps with the lower elevation limit of E. klamathense.

Recall from last month's discussion that Erythronium klamathense is though to be most similar (genetically, at least) to the common ancestor of all of the western erythroniums. This is perhaps another way to say that it is not a particularly distinctive species, with its plain green leaves and white flowers with yellow centers. Elmer Applegate noted that "this species is easily grown and very responsive to cultivation" (Applegate 1935), though because his garden was in Klamath Falls, Oregon, which has a rather arid montane climate, his results may not be typical of gardens in other temperate climates.

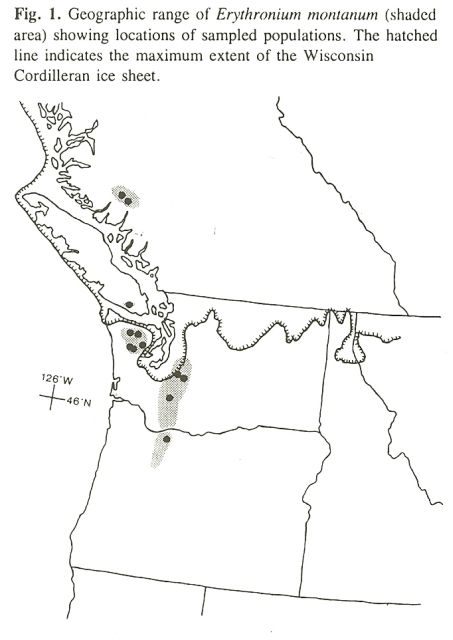

The crown jewel of western erythroniums has to be Erythronium montanum. "Montanum" is an appropriate specific epithet, for this species is never found below an elevation of about 3000 ft. (900 m.). Despite the fact that it occurs in the millions in suitable habitats, it actually has a somewhat limited geographic distribution. It is common in both the Cascade and Olympic Mountains of Washington, but occurs only in four counties in the Oregon Cascades, and is known from only two disjunct localities in British Columbia. Interestingly, E. montanum occurs primarily south of the southern limit of the continental ice sheet during the late Pleistocene, as shown on this map from a paper by Geraldine Allen and co-workers:

Geographic range of Erythronium montanum, from Allen et al. 1996

The map shows how the occurrences in British Columbia, on Vancouver Island and in the mainland Coast Ranges, are considerably disjunct from the main range of the species and are well north of the limit of the continental ice sheet. The evidence that Allen et al. (1996) gathered suggests that the B.C. populations arose by long-distance dispersal from southern refugia after the climate moderated during the Holocene.

I have seen E. montanum many times while hiking in the mountains in Washington, but was curious to see where it grows at the southern limit of its range in Oregon. I had heard about a locality in the Cascade Mountains of Marion County (east of Salem) at a place called Dogtooth Rock. With a name like "Dogtooth Rock", I figured that I had to check out - there aren't many places named after a biogeographically significant erythronium population!

It had been a rather rainy May, but on June 3rd the forecast was for dry weather and I figured I had a pretty good chance of finding the erythroniums in good condition. Dogtooth Rock is a 4500 ft. rocky knob along a steep sided ridge line. The precipitous topography affords excellent views, in this case looking southeast toward Mt. Jefferson and the crest of the Cascade Range. Dogtooth Rock is the knob on the left.

Dogtooth Rock, Cascade Mountains of Oregon

Dogtooth Rock itself does sort of resemble in shape the outline of a dormant erythronium corm. It lacks the subalpine meadows that are the typical habitat of Erythronium montanum. Instead, E. montanum occurs in small forest openings and north-facing rocky scree.

Erythronium montanum along the trail near Dogtooth Rock

It makes sense that E. montanum would be found in shady habitats and on north facing slopes at a site that is very close to the southernmost limit of the species' range, which only extends about 17 miles further to the south. It is curious that even at its southern limit, E. montanum occurs at a relatively low elevation (for this species). Such lower elevation populations may be useful as seed sources for plants that have a better chance of succeeding in gardens.

Fortunately the timing of my visit was good in terms of flowering phenology, but as there had been a rain shower overnight, the damp flowers were a bit droopy, and not quite in prime condition. However, if you pick a bouquet and let them dry out for a day, you can see their full charm.

Bouquet of Erythronium montanum flowers

Erythronium montanum is probably the largest-flowered of the western species. Note that the flowers show a bit of a "pinwheel" twist at the tips of the tepals, which is a unique characteristic of E. montanum. The leaves of E. montanum are of course plain and not mottled, and often exhibit an abrupt taper from the leaf blade to the petiole. Recall from last month's installment that the genetic studies show that E. montanum is most closely related to E. grandiflorum and E. idahoense.

I waited until late June to undertake my final road trip to California. In contrast to the Pacific Northwest, the winter of 2004-2005 was one of unusually high precipitation, and the mountains had a much deeper snowpack than usual. I wanted to find Erythronium purpurascens, a subalpine species of the northern Sierra Nevada, and my research indicated that it could be found in the mountains along I-80 west of Lake Tahoe.

Erythronium purpurascens is one of the more widespread of the Sierra Nevada erythroniums, and was one of the earliest western erythroniums to be collected and described. Recall from May's discussion that the five species of plain-leaved erythroniums form a closely related group of species that includes E. purpurascens, E. pluriflorum, E. pusaterii, E. tuolumnense, and E. taylori.

On June 29th I set out up the trail to Loch Leven Lakes amidst the magnificent granitic landscape of the high Sierra. This area is in the Tahoe National Forest of Placer County, about 170 miles east of San Francisco. The montane forest is dominated by red fir (Abies magnifica), with a number of other firs and pines mixed in.

Granitic landscape, Loch Leven Lakes trail

The trailhead is at an elevation of 5700 ft. (1740 m.), and the erythroniums at this elevation had bloomed some weeks earlier. However, once I was about 2/3 of the way up to the ridge crest (about 6400 ft./ 1950 m) there were still a few snow banks, and drifts of flowering Erythronium purpurascens appeared in areas where the snow had recently melted out.

The flowers of E. purpurascens are white with yellow centers. The tepals develop a pink or purplish tinge as they age, thus the epithet "purpurascens". What sets this species apart from others, however, is the diminutive size of the flowers. They are tiny! "Dainty" is a good word to use to describe the flowers of this species.

Erythronium purpurascens flowers

While the stems of "average" plants bore only one or two flowers, I found many vigorous plants with five, six, or even eight flowers on a stem.

Closer to the top of the ridge, there were sizable drifts of E. purpurascens growing in openings in the conifer forest, and even some nice patches in natural rock gardens, such as in this crevice between granite outcrops:

Erythronium purpurascens on granite rocks

While this species is said to lack reproduction by vegetative offsets, I did find a few clumps that looked very much like they were the result of vegetative increase from a single plant:

A clump of Erythronium purpurascens, presumably increasing from offsets

This particular plant had nine flowering stems, with mostly five to eight flowers per stem!

Although E. purpurascens itself is probably not particularly amenable to cultivation, it could be a useful species for hybridizers to use to increase floriferousness in cultivars for the garden. And even though E. purpurascens is not a rare local endemic, it was certainly was enjoyable to spend a day in its presence in the granitic terrain of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

It had been my intention from the outset to end my tour in Mt. Rainier National Park, Washington. At 14, 410 ft. (4392 m.), Mt. Rainier is the second highest mountain in the 48 contiguous states. Erythronium montanum is common here in the subalpine zone, and E. grandiflorum occurs as well, though less abundantly.

In a typical year in early July the subalpine meadows are finally melting out after eight or nine months of snow cover, and Erythronium montanum is prominent in the picture-postcard landscape. However, as this was an unusually light snow year, I was probably pushing it when I headed up on July 10 to look for flowering Erythronium montanum on Mt. Rainier. The weather was also iffy on that day, with thick clouds in the lowlands that portended rain and mist higher up on the mountain. Even on the NE (rainshadow) side of Mt. Rainier, along the trail to the meadows of Summerland, the ridges were shrouded with mist.

Erythronium montanum habitat on Mt. Rainier

And yes, when I finally reached an area where the snow had only recently melted, and the erythroniums were in full flower, they were a sad, soggy, droopy lot:

Hillside with Erythronium montanum in the rain

The remarkable thing about mountain weather is that it is so changeable. If you have a little patience, conditions can change from miserable to ideal in only 24 hours. Fortunately that was the case for me the following day, July 11th, when I drove up to Paradise Meadows, an extensive area of subalpine parkland on the south side of Mt. Rainer. The weather was sunny, the sky was blue, and the glaciers tumbling down from the summit of the volcano were reflected in the few remaining patches of Erythronium montanum.

Erythronium montanum in Paradise meadows, Mt. Rainier National Park

While the extensive meadows of blooming Erythronium montanum, which I had viewed at Paradise in previous years, were long past flowering, being in the presence of such scenic grandeur and botanical beauty gave me cause to reflect on my explorations of the four months since I began my quest on March 16th. Finally, here was Erythronium montanum showing its true personality, its jaunty demeanor under the subalpine sunshine.

Erythronium montanum

I had driven many thousands of miles across the American west, and had hiked many miles to find erythroniums of all persuasions at their floriferous best. I had observed and photographed 15 Erythronium taxa in bloom (13 species and two additional subspecies/varieties), in a wide range of landscapes and habitats across the western states. I might venture to claim that this is a world record for the number of erythronium taxa observed in the wild in a single year. However, even while this claim is open to dispute, there is ample room for some other intrepid botanist to exceed this tally, if they feel so compelled.

The diversity of the genus Erythronium is a wonder of evolution, a wonder to be thankful for. The message that kept coming back to me, on each and every day of my journey, is that there is definitely more than one way to find Paradise.

Trailside near Paradise, Mount Rainier National Park

References:

Allen, G.A., J.A. Antos, A.C. Worley, T.A. Suttill, and R.J. Hebda. 1996. Morphological and genetic variation in disjunct populations of the Avalanche lily Erythronium montanum. Can. J. Bot. 74:403-412.

^ back to the top ^

|